WELCOME TO COMMUNITY REPORTS BY CCC’S RESEARCH JUSTICE INSTITUTE! WE’VE LAUNCHED THIS NEW SERIES TO PROVIDE A CLOSER LOOK AT OUR RESEARCH EFFORTS AND HELP DEMYSTIFY THE WORLD OF DATA.

in this edition, our summer Intern Meilin Beloney unpacks key terms and topics at the heart of research justice.

Research justice 101: Key terms and readings to know

“Research justice” can sound like a big concept, but at its core it’s about valuing the lived experiences and desires of marginalized community members as essential pieces of evidence and data. Incorporating it into your research practices means ensuring meaningful community participation in every step of the research process. Furthermore, research justice centers the desires of communities as key to understanding their circumstances, rather than relying on narratives that present communities as broken or as problems (i.e., deficit narratives).

To gain a deeper understanding of what research justice is, the Research Justice Institute looks to the work of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) scholars and researchers. Read on to unpack four key terms, along with some suggested readings, that are integral to understanding research justice.

1.Research oppression

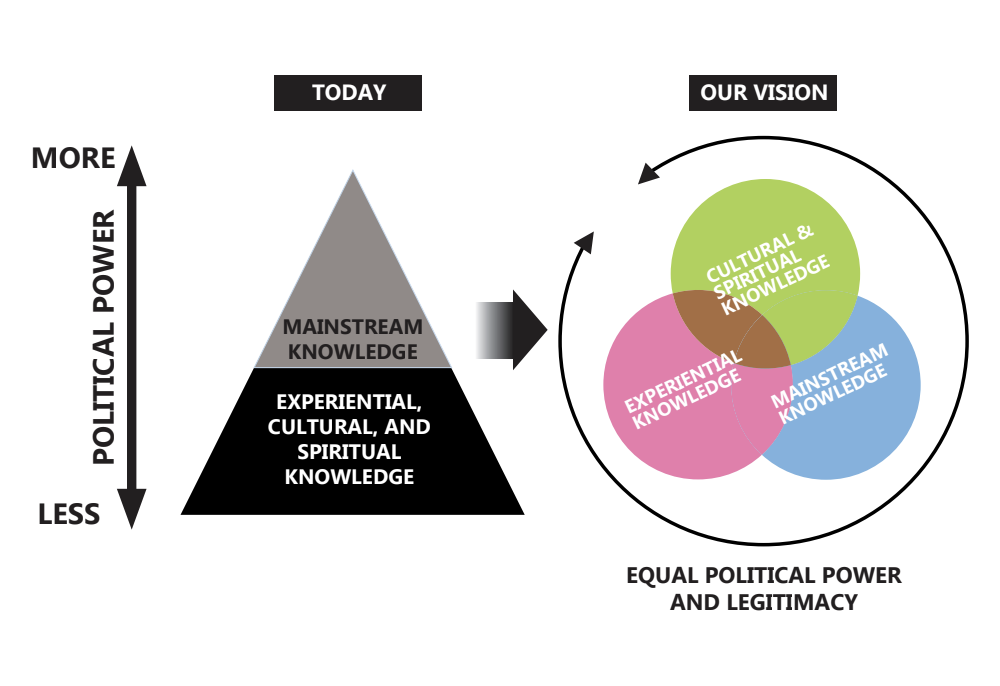

To understand research justice, it is important to start by unpacking what research justice is not. As pointed out by DataCenter in their 2015 report “Introduction to Research Justice,” there is a power imbalance within research practices, wherein dominant institutions control the production of knowledge, resulting in marginalized communities being unable to control or access information produced about them. Research oppression occurs when community members are viewed solely as subjects of research, rather than as active participants in the research process (DataCenter 2015). Social science research has long been used as a tool of oppression. In his book Thicker than Blood: How Racial Statistics Lie, Tufuku Zuberi points to the role that white supremacy plays in our understanding of society. White logic grants objectivity to white scholars while devaluing BIPOC experience and expertise, often framing it as too subjective or anecdotal. Community members’ lived experiences are dismissed as invalid to the research process, leading to dominant institutions controlling the data and the stories that are told about marginalized communities, without the community’s input (Zuberi 2001). When we refuse to use white supremacist logics and tools in our research practices, we envision an alternative to research oppression: research justice. Research justice places community experiences and desires at the forefront of the research process, uplifting community members as integral to every step. Research justice is a process and platform that affirms that marginalized communities are the experts in their own lives.

2.Dominant data vs community data

It is important to understand the distinction between dominant data and community data, and how each may be utilized to advance the aims of research justice. Dominant data is gathered by dominant institutions such as governments and universities, and is often gathered in service of the dominant institution. These data are typically gathered using large population-level surveys like the Census or through the collection of information an individual provides in exchange for a service (i.e., administrative data). Dominant data, which are often quantitative, can highlight trends within populations, but often perpetuates deficit narratives. Numbers and statistics do not always capture the social, political, economic, and historical contexts of the data, often leading to conclusions that lack nuance and place the blame on marginalized communities for their own marginalizations. For example, without the context of institutional racism, a statistic proving the high amount of police violence in Black neighborhoods might imply that Black neighborhoods are inherently dangerous, or that Black people themselves are violent, rather than acknowledging the many social and political factors that lead to over-policing of Black communities (Lanius 2015).

On the other hand, a key aspect of community data is that it is contextual. At CCC, we define community data as evidence generated by communities about their everyday lives, realities, and desires. Examples of evidence can include numbers, words, art, music, maps, and stories. Community data is collected, interpreted, and used on the terms of the community. By working with communities to understand their everyday experiences, we can gain a true sense of community needs and desires.

3.Community-led research

Community control is a key tenet of research justice. Research justice uplifts and values marginalized communities as experts of their own lived experiences and, therefore, as leading experts in how to improve their everyday realities and overall well-being. When conducting research with marginalized communities, it is important to not only include community members, but to treat them as authorities in the research process. Trust and collaboration between researchers and community members are paramount, as demonstrated through the work of anthropologist Mariana Mora. Mora worked with a Zapatista community in Chiapas, Mexico to shape her research on Zapatista politics, autonomy, and self-determination. In her article “The Production of Knowledge on the Terrain of Autonomy: Research as a Topic of Political Debate”, Mora takes readers through her research process, describing the ways in which community members helped to shape and evaluate her research at every step, from research design to reviewing drafts of her 2017 book, Kuxlejal Politics: Indigenous Autonomy, Race, and Decolonizing Research in Zapatista Communities. Mora’s experience highlights the importance of community-led research, and provides a key example of how research can be designed and conducted in collaboration with community members.

4.Damage- vs desire-centered research

In an open letter to communities, researchers, and educators, Eve Tuck, Unangax̂ scholar, calls for a moratorium on damage-centered research – research that documents pain and oppression in an attempt to leverage change for marginalized communities. Tuck argues that damage-centered research frames marginalized communities as depleted and broken, perpetuating deficit narratives and defining communities solely by their marginalization. Tuck instead proposes a desire-based framework for research, in which lived realities are acknowledged alongside hopes and visions for the future (Tuck 2009). Research justice should employ a desire-based framework in order to avoid framing marginalized communities solely by what they lack, and to acknowledge the full spectrum of inequality, oppression, wisdom, hope, and the potential for change that exists within all communities.

Check out RJI’s reading library to dig deeper into these concepts and more:

These concepts and readings provide an overview of the key components of research justice, and it is only the tip of the iceberg. To continue exploring these ideas and access a wider range of resources, we encourage you to visit our growing RJI Zotero library.